Abandoned Communities ..... Stowe

During the sixteenth century the typical medieval pattern of agriculture still existed at Stowe. Peasant farmers would have had a small plot of land in the village on which they had their home, grew vegetables, and kept a pig or a few poultry. In addition they would have been allowed to farm an allotted share of the communal fields. Within the parish as a whole there were communal open fields associated with the village of Dadford, and Boycott had its own field system, but Stowe and Lamport shared their fields.

Ridge and furrow surfaces can still be seen in several parts of the parish, a good example being on the hillside south west of Dadford around OS SP663381.

In 1633 a survey of most of the parish was carried out for the Temple family. It gives the names of the three fields shared by Stowe and Lamport as Windmill Field, Stockhold Field, and Netherfield, but the location of these fields is not known.

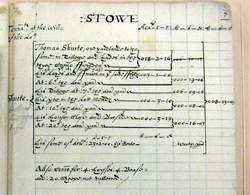

The survey of 1633, like William Sherytt’s will, can be seen at the Buckinghamshire Archives (ref. D104/73). It was compiled by a Mr Allen with the aim of guiding Sir Peter Temple’s development of his estate. On the pages referring to the manor of Stowe it lists 19 tenants. There is half a page on each tenancy, with a summary of its holdings, their size in acres, roods, and perches, and their value in pounds, shillings, and pence. The entry for Thomas Shurte is reproduced on the left. You can see that Thomas Shurte’s holdings amounted to just over 23 acres. I assume that the first item, 18 acres, 2 roods, and 16 perches in size, refers to Thomas Shurte’s share of the open fields, and the three acres or so following it may be the plot where his house was, but I would be grateful to receive any attempt to transcribe the details of this entry.

The allocation of land in Stowe manor is summarised on page 14 of the 1633 survey. The 19 tenants shared 298 acres, while demesne lands, those directly managed by the landowner, covered 724 acres. In addition 324 acres were occupied by coppices. Coppices were areas of woodland used both for hunting and for timber. In addition livestock and deer were permitted to graze in the coppices, though only during certain seasons and once the trees were well established. Young trees were protected from grazing animals by banks, ditches, and hedges.

The woodland would have supported a range of occupations. Those listed in Mark Page’s article include carpenter, cooper, sawyer, wheelwright, bird catcher, charcoal burner, potter, rope maker, and blacksmith.

In addition to land owned by the lord of the manor there was land owned by the religious authorities. The church itself served as the place of worship for the whole parish. It is the only medieval building to have survived to the present day. A glebe terrier of 1607 informs us that a vicarage was situated north of the churchyard. The grounds of the vicarage, just over an acre, included a walled garden and a hedged orchard. The vicarage itself was a substantial building of 15 rooms and two storeys. It was roofed partly with tiles and partly with thatch.

A transcription of the glebe terrier can be found in M Reed (Ed.), Buckinghamshire Glebe Terriers 1578-1640, Buckinghamshire Record Society 1997, Volume 30. The glebe terrier referring to Stowe is on page 194.

It is assumed that the village of Stowe lay next to the church, but its precise location is not known. No traces of it have remained on the surface, and archaeological investigations have so far not revealed clear evidence of medieval buildings. An estate map of about 1680 shows a road called Hey Way running north to south close to the eastern side of the church. It may have been the main road through the village, on the south leading to the town of Buckingham roughly two and a half miles away. The same map indicates another road, the Slant Road, leaving the Hey Way in a westerly direction about a hundred metres south of the church.

Ridge and furrow surfaces can still be seen in several parts of the parish, a good example being on the hillside south west of Dadford around OS SP663381.

In 1633 a survey of most of the parish was carried out for the Temple family. It gives the names of the three fields shared by Stowe and Lamport as Windmill Field, Stockhold Field, and Netherfield, but the location of these fields is not known.

The survey of 1633, like William Sherytt’s will, can be seen at the Buckinghamshire Archives (ref. D104/73). It was compiled by a Mr Allen with the aim of guiding Sir Peter Temple’s development of his estate. On the pages referring to the manor of Stowe it lists 19 tenants. There is half a page on each tenancy, with a summary of its holdings, their size in acres, roods, and perches, and their value in pounds, shillings, and pence. The entry for Thomas Shurte is reproduced on the left. You can see that Thomas Shurte’s holdings amounted to just over 23 acres. I assume that the first item, 18 acres, 2 roods, and 16 perches in size, refers to Thomas Shurte’s share of the open fields, and the three acres or so following it may be the plot where his house was, but I would be grateful to receive any attempt to transcribe the details of this entry.

The allocation of land in Stowe manor is summarised on page 14 of the 1633 survey. The 19 tenants shared 298 acres, while demesne lands, those directly managed by the landowner, covered 724 acres. In addition 324 acres were occupied by coppices. Coppices were areas of woodland used both for hunting and for timber. In addition livestock and deer were permitted to graze in the coppices, though only during certain seasons and once the trees were well established. Young trees were protected from grazing animals by banks, ditches, and hedges.

The woodland would have supported a range of occupations. Those listed in Mark Page’s article include carpenter, cooper, sawyer, wheelwright, bird catcher, charcoal burner, potter, rope maker, and blacksmith.

In addition to land owned by the lord of the manor there was land owned by the religious authorities. The church itself served as the place of worship for the whole parish. It is the only medieval building to have survived to the present day. A glebe terrier of 1607 informs us that a vicarage was situated north of the churchyard. The grounds of the vicarage, just over an acre, included a walled garden and a hedged orchard. The vicarage itself was a substantial building of 15 rooms and two storeys. It was roofed partly with tiles and partly with thatch.

A transcription of the glebe terrier can be found in M Reed (Ed.), Buckinghamshire Glebe Terriers 1578-

It is assumed that the village of Stowe lay next to the church, but its precise location is not known. No traces of it have remained on the surface, and archaeological investigations have so far not revealed clear evidence of medieval buildings. An estate map of about 1680 shows a road called Hey Way running north to south close to the eastern side of the church. It may have been the main road through the village, on the south leading to the town of Buckingham roughly two and a half miles away. The same map indicates another road, the Slant Road, leaving the Hey Way in a westerly direction about a hundred metres south of the church.

Two

The tenancy of Thomas Shurte

The contents of Stowe manor in 1633

Stowe parish church

The interior of the church, showing the south aisle. If you go there, pause to admire the engraved window, done by Laurence Whistler.

A very old yew tree, close to the western end of the churchyard. Stowe House can just be seen in the distance.