Imber is a small village on Salisbury Plain, at OS ST965486. Some of its buildings

still exist, but since 1943 no one has lived there. In this section we will consider

what type of village it was and mention some of the people who lived there. Its takeover

by the military authorities will be described. But we will also be interested in

the way that Imber has stayed in the news since its abandonment. At first campaigns

were mounted with the aim that residents might be allowed to return. More recently,

as the hope of re-

At the outset I have to acknowledge that much of the information in this section comes from Rex Sawyer’s superb book Little Imber on the Down, published by Hobnob Press.

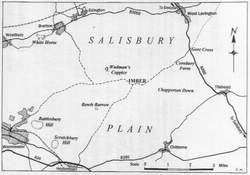

The origins of Imber are not recorded, but we know that it was a significant settlement by the Saxon period and it receives a mention in the Domesday Book of 1086. It was always an isolated community, lying six miles east of the town of Warminster and some four miles from neighbouring villages such as Heytesbury, Edington and Bratton. For most of its history it was connected to these places only by rough tracks which in many places had to be marked by piles of chalk stones. Its existence depended on agriculture, a balance of arable farming and livestock.

It is the kind of place that easily lends itself to fantasies of a quiet, undisturbed, and unchanging rural lifestyle. In order to counter such fantasies I will highlight some of the hazards faced by the people of Imber over the centuries:

· Flooding. Imber lies in a valley whose watercourse is the Imber Dock. During the summer the Imber Dock tends to dry out, but after heavy rain huge amounts of water flow along it. Records from the second half of the eighteenth century reveal that during that period floods caused frequent devastation and some loss of life. In 1757, for example, the walls of cottages close to the Imber Dock were undermined, several of them collapsed, and it was said that a number of inhabitants died. After heavy falls of snow in the winter of 1773 the process of thawing gave rise to floods that swept away and completely destroyed two dwellings.

· Fire. A major fire incident occurred in June 1770, but an appeal for financial assistance was publicised over a wide area and money was distributed to those who had suffered losses. A century and a half later the villagers were celebrating the Silver Jubilee of George V when a barrel of tar fell off the top of a bonfire, causing great alarm as it rolled down the hillside. In 1920 the manor house, Imber Court, was bought by the Holloway family, but in the course of renovations the house was largely destroyed by a fire thought to have been started by a workman’s torch. Two local men saw the flames through a window and raised the alarm, but Imber was too far from fire fighting services for the house to be saved. It had to be completely rebuilt.

· Robbery. As early as the sixteenth century Salisbury Plain in general was renowned for armed attacks. Its isolation, the prospect of meeting a farmer carrying money after selling livestock or farm produce, and the possibility of making a rapid getaway made it attractive to highwaymen. A famous incident took place on 21 October 1839. The precise sequence of events remains vague, but Matthew Dean of Imber was attacked by four men while on his way home from Devizes market. He called out “George, George”, and the men, deceived into thinking that someone else was nearby, attempted to escape. After a three hour chase it is said that one of the robbers, Benjamin Colclough, collapsed and died, and the other three were arrested. They were sentenced to transportation.

Photographs of two stones erected to commemorate this incident can be seen on the Chitterne website.

· Punctured bicycle tyres. Frank Maidment, as well as being a sub-