Charlton was a village in Gloucestershire, just north of Bristol. It was removed in 1946 as the land was needed for an extension to Filton airfield, from where test flights of the Brabazon aeroplane were due to take place.

June Keating has described the village and supplied reminiscences from many people who knew Charlton in four booklets: The Village that Died (published in 1995), Memories Fifty Years On (1998), Reunions and Rememberances (2001), and The Phoenix (2008). A leaflet entitled Charlton Walk, describing a walk around the perimeter of the airfield, can be obtained from South Gloucestershire Council.

Mwldan Isaf, or Lower Mwldan, was a district of the town of Cardigan where the Mwldan

stream flowed into the river Teifi. Among the warehouses and ship-

Idris Mathias, born in Foundry Court in 1924, has written a vivid and moving account of his childhood in the Lower Mwldan in The Last of the Mwldan, published by Gomer in 1998.

Today the area is occupied by a supermarket and a large car park. A public toilet stands on the spot where the Mathias family lived.

Not many deserted medieval villages have been excavated by archaeologists. Guy Beresford

has reported on his investigations at Goltho and Barton Blount in The Medieval Clay-

Goltho in Lincolnshire and Barton Blount in Derbyshire both lay on clay soil. Beresford’s report describes building materials (very little stone, some use of timber) and construction techniques, and gives detailed information about objects found at both sites. Beresford proposed that as the climate became wetter during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries people reliant on arable farming moved away first and then those who owned livestock also departed.

There was a large colliery at North Seaton in Northumberland. At its height in the 1920s it employed over a thousand staff. A village was built close to the mine to provide accommodation to miners and their families. The colliery closed in 1961, and then in 1969 the village was demolished apart from two streets at the eastern end.

Was There Ever Railway Row? by Mike Kirkup, published by Woodhorn Press in 1997, contains much information about North Seaton colliery and the village, together with photographs, a list of voters in 1885, extracts from diaries, articles from local newspapers, and the personal memories of former residents.

I didn’t think there were many deserted villages in Bedfordshire until I came across Lost Villages of Bedfordshire by Dick Dawson, second edition published by Streets Publishers in 2008. Read Dawson and you will learn about Potsgrove, Stratton, Chellington, Chalgrove, and thirteen other villages. Dawson is especially good at describing the details of isolated churches and giving biographical information about some of the people named on stone and brass memorials.

In July 1942 the Ministry of Defence took over a large area north of Thetford in Norfolk and converted it into the Stanford Training Area. Residents were obliged to leave farms and small villages including Stanford, Tottington, and West Tofts.

The one and only Lucilla Reeves, who lived at Bagmore Farm, wrote a personal account of the evictions, Farming on a Battle Ground by A Norfolk Woman. It was published after Lucilla Reeves took her life in 1950, and then printed again by George R Reeve Ltd. in 2000.

The villages of Derwent and Ashopton in Derbyshire were demolished in the early 1940s in order to create Ladybower reservoir. A history of the villages and an account of the building of the reservoir appears in Silent Valley Revisited by Vic Hallam, published by Sheaf Publishing in 2002. Plenty of good photographs.

The hamlet of Burnside of Dun lay a few miles west of Montrose in Angus. In the middle of the nineteenth century about sixty people lived there. However, with the decline of domestic handloom weaving and fewer jobs in farming inhabitants gradually moved away in search of employment elsewhere.

Catherine Rice’s book All their Good Friends and Neighbours: The Story of a Vanished Hamlet in Angus makes excellent use of census information and other records to throw light on the way of life of the people of Burnside and the social circumstances in which they lived. It is published by the Abertay Historical Society.

Once Upon A Hill, edited by Peter Francis and Tom Wall, tells the story of the lost communities of the Stiperstones. When lead mining thrived on the slopes of the Stiperstones hill range in Shropshire several small villages and hamlets developed to house the miners and their families. Lead mining came to an end in the early twentieth century, and several of the communities, including Blakemoregate, Perkins Beach, and The Bog, were gradually abandoned.

The former school at The Bog has been turned into an excellent visitor centre..

The books listed below describe abandoned villages not featured elsewhere in this website.

If you have difficulty getting hold of any of these books then please get in touch with me.

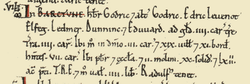

Domesday entry for Barton Blount