Abandoned Communities ..... Rosedale

We now come to the closure of the mines and the railway. In 1873 the Rosedale mines produced over half a million tons of ironstone. That was the most successful year in its history. During the following six years production fell steadily as a result of a prolonged depression in the iron trade. In January 1879 the Rosedale and Ferryhill Iron Company were forced to suspend production. The mines opened again at the end of 1880, but production never again reached the level of the early 1870s.

The first mine to close was Hollins, where production came to an end in 1885. It is not clear whether the remaining ironstone deposits had become too inaccessible and unproductive or whether other factors may have hastened the closure of Hollins Mine.

Next to close was Sheriff’s Pit, in 1911. As mining had proceeded the seam of ironstone had become narrower, and at Sheriff’s Pit the infiltration of water caused major difficulties.

The East Mines were given a boost during the First World War when the demand for iron was high. Thereafter the East Mines struggled to remain profitable. The price of iron fell sharply in 1921, and the number of staff employed went from 177 underground and 24 on the surface to 42 and 11. Mining ceased entirely as a result of the General Strike of 1926, and never began again. The East Mines were officially abandoned on 28 February 1928.

The railway survived a little longer. During the 1920s it was found that the waste from the calcining kilns could be sold at a profit, and the railway continued to be used to transport it away until the end of October 1928. On 8 June 1929 the last locomotive, No. 1893, was lowered down the Ingleby Incline.

The number of staff employed in the mines and on the railway fell gradually from 1885 to 1929. Some of those made redundant, such as the engine driver Willy Wood stayed in Rosedale, but most moved away in search of work elsewhere. Enos Lythe, for example, lived at Hill Cottages with his wife Martha and their children, Fred, born in 1918, and twins Lily and Rose, born in 1920. In 1927 they moved to Armthorpe near Doncaster, where Enos obtained employment at Markham Main colliery.

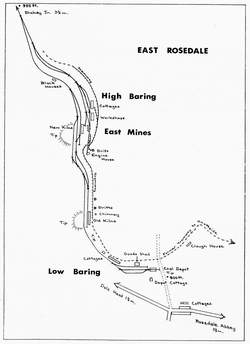

I stayed in Rosedale for three days in October 2009. A highlight of my stay was a guided walk organised by the Rosedale History Society and led by Patrick Chambers. We walked up the east side of Rosedale from School Row and Hill Row, and past the site of the railway depot, coal bunkers and goods shed. Then we took the tramway route past a ventilator stack, two of the entrances to the East Mines, the explosives store and the electricity generating shed. Miners collecting explosives from the store were required to pay for it. We continued up the tramway to the ruins of some workshops and the row of cottages at High Baring. From there we walked down the slope to the track of the railway, and came back past the two sets of calcining kilns. We learnt that the argument over which set of calcining kilns is older is by no means settled.

For more information on the Rosedale History Society go to the website of the Rosedale Parish Council. The Rosedale Railway website has a lot more information on the railway and the iron mines. Several websites describe walks in Rosedale and have photographs of the industrial remains that can still be seen. The North York Moors CAM website, run by Don Burluraux, has a page on Rosedale.

The first mine to close was Hollins, where production came to an end in 1885. It is not clear whether the remaining ironstone deposits had become too inaccessible and unproductive or whether other factors may have hastened the closure of Hollins Mine.

Next to close was Sheriff’s Pit, in 1911. As mining had proceeded the seam of ironstone had become narrower, and at Sheriff’s Pit the infiltration of water caused major difficulties.

The East Mines were given a boost during the First World War when the demand for iron was high. Thereafter the East Mines struggled to remain profitable. The price of iron fell sharply in 1921, and the number of staff employed went from 177 underground and 24 on the surface to 42 and 11. Mining ceased entirely as a result of the General Strike of 1926, and never began again. The East Mines were officially abandoned on 28 February 1928.

The railway survived a little longer. During the 1920s it was found that the waste from the calcining kilns could be sold at a profit, and the railway continued to be used to transport it away until the end of October 1928. On 8 June 1929 the last locomotive, No. 1893, was lowered down the Ingleby Incline.

The number of staff employed in the mines and on the railway fell gradually from 1885 to 1929. Some of those made redundant, such as the engine driver Willy Wood stayed in Rosedale, but most moved away in search of work elsewhere. Enos Lythe, for example, lived at Hill Cottages with his wife Martha and their children, Fred, born in 1918, and twins Lily and Rose, born in 1920. In 1927 they moved to Armthorpe near Doncaster, where Enos obtained employment at Markham Main colliery.

I stayed in Rosedale for three days in October 2009. A highlight of my stay was a guided walk organised by the Rosedale History Society and led by Patrick Chambers. We walked up the east side of Rosedale from School Row and Hill Row, and past the site of the railway depot, coal bunkers and goods shed. Then we took the tramway route past a ventilator stack, two of the entrances to the East Mines, the explosives store and the electricity generating shed. Miners collecting explosives from the store were required to pay for it. We continued up the tramway to the ruins of some workshops and the row of cottages at High Baring. From there we walked down the slope to the track of the railway, and came back past the two sets of calcining kilns. We learnt that the argument over which set of calcining kilns is older is by no means settled.

For more information on the Rosedale History Society go to the website of the Rosedale Parish Council. The Rosedale Railway website has a lot more information on the railway and the iron mines. Several websites describe walks in Rosedale and have photographs of the industrial remains that can still be seen. The North York Moors CAM website, run by Don Burluraux, has a page on Rosedale.

Five

East Rosedale

Coal Bunkers at the railway terminus at East Rosedale

Remains of a workshop at the East Mines

Memorial bench between Bank Top and Blakey Junction. The verse continues on the other side: Work shift over, in the sun, on the hill having fun.

Rosedale.

To experience the full splendour of this picture click on it, wait a few seconds while it downloads, and then zoom in and pan around.