Abandoned Communities ..... Palmer’s Village

In 1853 Charles Manby Smith wrote a quite wonderful description of “A Deserted Village in London”, a place known as Palmer’s Village. He tells us that he had lived in the village during many happy years of his youth, some twenty or thirty years earlier. He deplored the way that the village had been swallowed up by the expansion of London and then disappeared altogether when Victoria Street was created between 1845 and 1851.

“A Deserted Village in London” is a chapter in Charles Manby Smith’s “Curiosities of London Life”. You can read it on the Victorian London website.

The story of Palmer’s Village begins in 1656 with the founding of a school for 20 boys and almshouses for 12 elderly people by Rev. James Palmer. I am going to take the liberty of quoting in full the tribute to James Palmer that formed part of his memorial when his remains were buried in St Margaret’s Church, Westminster:

Heerunder is interred ye body of James Palmer Batchelor in Divinity borne in this parish of St Margarets in July 1595. A most pious and charitable man exprest in severall places by many remarkeable actions & particularly to this parish in building fayer almes houses for 12 poor olde people with a free school and a comodious habitation for the scoolmaster and a convenient chappell for prayers and preaching where he constantly for divers yeares before his death once a week gave a comfortable sermon. He indowed ye same with a competent yearly revinew of free hold estate comitted to ye trust & care of 10 considerable persons of ye place to be renewed as any dye. He cheerfully ended this life ye 5 of January 1659.

Palmer’s almshouses were built at the western end of Westminster, adjacent to the burial ground for the parish of St Margaret’s. They occupied a strip of land at the north eastern corner of Tothill Fields, a large area of scattered market gardens among waste ground that became marshy during wet weather. A lot of shooting went on in Tothill Fields. Men would go there to practice shooting, an activity still commemorated in the name of Artillery Row. Those who lacked peaceful means of dealing with disputes would go there to resolve their quarrels by duelling.

For a general history of Westminster, and many excellent illustrations, go to Isobel Watson’s book, Westminster and Pimlico Past, Historical Publications, 1993.

In the seventeenth century any provision of education or housing for poor people relied upon the philanthropy of wealthy benefactors. In 1600 Emanuel Hospital had been founded a little further west where the St James’ Court Hotel now stands. Endowed by Lady Ann Dacre, it provided accommodation for ten men and ten women. Other almshouses were established close to Palmer’s almshouses, including a group on Rochester Row endowed by Emery Hill in 1674 but not built until 1708.

All these foundations had educational aims in addition to the provision of almshouses. For various reasons, generally financial but sometimes because a schoolmaster became disabled, there were long periods when the educational service was suspended. They usually maintained their obligation to give accommodation to elderly people, though when money was especially tight the number of residents might fall below the number specified in the endowment.

A lot of information about the almshouses and schools created by James Palmer and Emery Hill can be found in the Reports of the Commissioners on Charities and Education of the Poor, Volume 22, published in 1839. You can read these reports at the City of Westminster Archives Centre.

“A Deserted Village in London” is a chapter in Charles Manby Smith’s “Curiosities of London Life”. You can read it on the Victorian London website.

The story of Palmer’s Village begins in 1656 with the founding of a school for 20 boys and almshouses for 12 elderly people by Rev. James Palmer. I am going to take the liberty of quoting in full the tribute to James Palmer that formed part of his memorial when his remains were buried in St Margaret’s Church, Westminster:

Heerunder is interred ye body of James Palmer Batchelor in Divinity borne in this parish of St Margarets in July 1595. A most pious and charitable man exprest in severall places by many remarkeable actions & particularly to this parish in building fayer almes houses for 12 poor olde people with a free school and a comodious habitation for the scoolmaster and a convenient chappell for prayers and preaching where he constantly for divers yeares before his death once a week gave a comfortable sermon. He indowed ye same with a competent yearly revinew of free hold estate comitted to ye trust & care of 10 considerable persons of ye place to be renewed as any dye. He cheerfully ended this life ye 5 of January 1659.

Palmer’s almshouses were built at the western end of Westminster, adjacent to the burial ground for the parish of St Margaret’s. They occupied a strip of land at the north eastern corner of Tothill Fields, a large area of scattered market gardens among waste ground that became marshy during wet weather. A lot of shooting went on in Tothill Fields. Men would go there to practice shooting, an activity still commemorated in the name of Artillery Row. Those who lacked peaceful means of dealing with disputes would go there to resolve their quarrels by duelling.

For a general history of Westminster, and many excellent illustrations, go to Isobel Watson’s book, Westminster and Pimlico Past, Historical Publications, 1993.

In the seventeenth century any provision of education or housing for poor people relied upon the philanthropy of wealthy benefactors. In 1600 Emanuel Hospital had been founded a little further west where the St James’ Court Hotel now stands. Endowed by Lady Ann Dacre, it provided accommodation for ten men and ten women. Other almshouses were established close to Palmer’s almshouses, including a group on Rochester Row endowed by Emery Hill in 1674 but not built until 1708.

All these foundations had educational aims in addition to the provision of almshouses. For various reasons, generally financial but sometimes because a schoolmaster became disabled, there were long periods when the educational service was suspended. They usually maintained their obligation to give accommodation to elderly people, though when money was especially tight the number of residents might fall below the number specified in the endowment.

A lot of information about the almshouses and schools created by James Palmer and Emery Hill can be found in the Reports of the Commissioners on Charities and Education of the Poor, Volume 22, published in 1839. You can read these reports at the City of Westminster Archives Centre.

One

The memorial to James Palmer on the north wall of St Margaret’s Church, Westminster.

It was damaged by an oil bomb on 25 September, 1940.

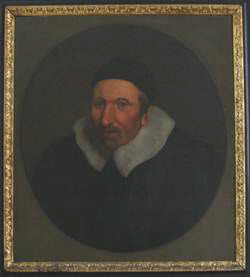

Portrait of James Palmer, now hanging in the committee room of the Westminster Almshouses Foundation.

It may have been painted by Peter Lely, but is more likely to have been done by one of his followers.

The rear of Palmer’s Almshouses

Part of the front

The chapel

These drawings were done by William Capon in 1817, just before the almshouses were rebuilt. The pencil notes indicate that they were intended to be sketches for a series of paintings, but I do not know if the paintings were completed.

These images are used with the permission of the City of Westminster Archives Centre.