Abandoned Communities ..... Cosmeston

The reconstruction of the byre in the farmstead has been described in the article by Newman and Parkhouse mentioned above. Lias limestone was used for the walls, much of it taken from a nearby beach, a source that was also used in the original construction. The roof timbers were made out of elm obtained from local woods and marshes. Hazel and willow were used for thatching spars. Some of the thatching reed was brought from Cosmeston country park, some from other wetlands in South Wales. Quantities of materials and the amount of time needed to complete sections of the work were recorded. The byre required 56 tons of stone to build the two main walls 1.64 metres high and gables at each end that rose to 4.3 metres. Its roof area is 56 square metres. It took 360 hours to cut enough reed to cover it, and about 180 hours to put the thatch in place. We are told that the workforce involved in the thatching may have been similar to that available in the Middle Ages. It comprised one skilled craftsman and two or three “inexperienced but adaptable” assistants.

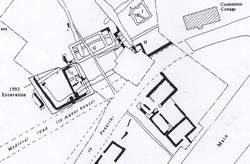

Newman and Parkhouse also report the initial phases of excavation on the north west side of the road. Apart from a couple of post-medieval buildings the first building to be revealed was a large structure with evidence of an internal dividing wall (Building G). Some indications of an external stairway were found, suggesting that the building had two storeys or at least a loft. Building G has been the subject of a series of alternative interpretations. Newman and Parkhouse proposed that it might be a public building such as a hall. Subsequently, however, another building was found close to Building G. This building, Building L, was thought to be a dwelling, with a courtyard and a small semi-circular outbuilding that may have housed a farm animal. Buildings G and L were then interpreted as forming a similar farm complex to that discovered on the other side of the road, Building G now being assumed to be a barn.

The excavation of Building L and the structures associated with it has been reported by Coles N R, Cosmeston, Archaeology in Wales, 1988, 28, 72 and by Andrews P, Excavations at Cosmeston Medieval Village 1993, Archaeology in Wales, 1996, 36, 11-35..

Buildings G and L have been reconstructed, and the small outbuilding has been designated as a pigsty. Visitors may sometimes see it occupied by a pig. Building G has been assigned a purpose which I assume goes well beyond the evidence, but can perhaps be justified on educational grounds. It is now a tithe barn. It contains the only waxwork model at Cosmeston, the figure of a retired priest who manages the barn and ensures that tithes are brought to it by all who owe them. The priest is most often known as Lorenzo, named after a former member of staff at Cosmeston. Occasionally he becomes Roger.

Visit the village today, and you will find yourself bringing to it a twenty first century understanding of the world while having to deal with a concerted attempt by costumed staff members to make you look at everything through the eyes of a citizen of the fourteenth century. For those, like myself, who lack role playing skills it tends to be a deeply confusing experience.

On entry to the village you will see a notice warning you that your actions may be monitored by closed circuit television. You may then overhear a group of schoolchildren being told by a peasant not to remove straw from the thatched roofs, “If you do, I’ll come to your house and remove some tiles.” The group’s teacher may be heard to urge “When you’ve dumped your bags let’s go, we haven’t got all day.” Peasants may be seen slipping behind a dwelling for a quick cigarette. If you happen to be there on the same day as Lord Richard of Hennessy you may notice Lord Richard nudging his Lady to let her know that her photograph is about to be taken. On one occasion I was not allowed to enter the bakery as the fire had become too hot and the door to the stove had been burnt. This would not have happened if Gareth the baker had been at home, but he was “away in America” at the time.

Experienced members of staff are proficient at knowing when to continue in their fourteenth century role and when visitors have a query that assumes a modern perspective. Younger actors, such as the baker’s daughter, may not always get it right. On a visit when the baker’s wife and the baker’s daughter were busy kneading dough I asked the baker’s daughter how long she had been doing this. The baker’s daughter appeared thrown by this query, but the baker’s wife stepped in to tell me that her daughter had probably been doing it since she was about six.

Experienced members of staff have a large repertoire of conversational gambits, but after more than a couple of visits you will start to notice that certain themes tend to be repeated. More than once a peasant’s wife has observed that I wear glasses and pointed out that I must be moderately wealthy in order to be able to afford glass upon my face. I am likely to be asked where I come from, and on giving the reply I will be advised that I should be able to get home by nightfall. Ten year old female visitors will be informed, in a slightly ominous tone of voice, that they are likely to find themselves married within two years.

Newman and Parkhouse also report the initial phases of excavation on the north west side of the road. Apart from a couple of post-

The excavation of Building L and the structures associated with it has been reported by Coles N R, Cosmeston, Archaeology in Wales, 1988, 28, 72 and by Andrews P, Excavations at Cosmeston Medieval Village 1993, Archaeology in Wales, 1996, 36, 11-

Buildings G and L have been reconstructed, and the small outbuilding has been designated as a pigsty. Visitors may sometimes see it occupied by a pig. Building G has been assigned a purpose which I assume goes well beyond the evidence, but can perhaps be justified on educational grounds. It is now a tithe barn. It contains the only waxwork model at Cosmeston, the figure of a retired priest who manages the barn and ensures that tithes are brought to it by all who owe them. The priest is most often known as Lorenzo, named after a former member of staff at Cosmeston. Occasionally he becomes Roger.

Visit the village today, and you will find yourself bringing to it a twenty first century understanding of the world while having to deal with a concerted attempt by costumed staff members to make you look at everything through the eyes of a citizen of the fourteenth century. For those, like myself, who lack role playing skills it tends to be a deeply confusing experience.

On entry to the village you will see a notice warning you that your actions may be monitored by closed circuit television. You may then overhear a group of schoolchildren being told by a peasant not to remove straw from the thatched roofs, “If you do, I’ll come to your house and remove some tiles.” The group’s teacher may be heard to urge “When you’ve dumped your bags let’s go, we haven’t got all day.” Peasants may be seen slipping behind a dwelling for a quick cigarette. If you happen to be there on the same day as Lord Richard of Hennessy you may notice Lord Richard nudging his Lady to let her know that her photograph is about to be taken. On one occasion I was not allowed to enter the bakery as the fire had become too hot and the door to the stove had been burnt. This would not have happened if Gareth the baker had been at home, but he was “away in America” at the time.

Experienced members of staff are proficient at knowing when to continue in their fourteenth century role and when visitors have a query that assumes a modern perspective. Younger actors, such as the baker’s daughter, may not always get it right. On a visit when the baker’s wife and the baker’s daughter were busy kneading dough I asked the baker’s daughter how long she had been doing this. The baker’s daughter appeared thrown by this query, but the baker’s wife stepped in to tell me that her daughter had probably been doing it since she was about six.

Experienced members of staff have a large repertoire of conversational gambits, but after more than a couple of visits you will start to notice that certain themes tend to be repeated. More than once a peasant’s wife has observed that I wear glasses and pointed out that I must be moderately wealthy in order to be able to afford glass upon my face. I am likely to be asked where I come from, and on giving the reply I will be advised that I should be able to get home by nightfall. Ten year old female visitors will be informed, in a slightly ominous tone of voice, that they are likely to find themselves married within two years.

Three

A plan showing buildings G and L

The pigsty

Lorenzo

Lord Richard of Hennessy and Lady Ingrid, with the Tithe Barn in the background