Abandoned Communities ..... St Kilda

Having mentioned a story which you may or may not have believed, I hope you will permit me to indulge in a short digression on the subject of myths and legends. You may have noticed that in general I have refrained from passing on such stories. I have not told you about church bells ringing under the water or lovers doomed in their attempts to form a closer relationship by the class differences of their families of origin. In my view such stories are objectionable, not just because there is rarely evidence for their truth, but more because they are generally told in a tone that conveys a perception of the community under discussion as quaint, gullible, stupid, or in other respects inferior.

Having said that, I want to share with you two of the legends of St Kilda, the first because it illustrates the tendency for an almost identical legend to become associated with several geographically separate communities, the second because I like it.

The first legend deals with the way in which St Kilda came into the ownership of the MacLeod family. As the MacDonalds also laid claim to the islands it was agreed that a boat race would take place and the islands would be awarded to the crew that first laid a hand on St Kilda. As both boats approached the shore the MacLeod boat was a little way behind, but a member of their crew cut off one of his hands and with his other hand threw it onto the land. The trouble with this tale is that, as shown by Mary Harman, a similar story has been told of two other places in Scotland and also two places in Ireland.

Mary Harman, op. cit. p230.

The other story relates to a place known as the Lover’s Stone or the Mistress Stone, a rocky ledge on a hill on the south side of Hirte from which there is a sheer drop of 135 metres into the sea. A ritual said to have taken place there at some time in the past was described by Robert Connell in 1887 as follows: “In those days a young St. Kildan who wished to make one of the fair maids of the island his own was required to accomplish a most dangerous feat in order to prove possibly the sincerity of his love, but, more probably, his ability to support a wife. The aspirant to the hand of a fair St. Kildan had to climb this giddy, dangerous height, and, planting his left heel on the outer edge, with the sole of his foot entirely unsupported, he extended his right leg forward beyond the other and grasped the foot with both hands, holding it long enough to satisfy the lady and her friends gathered below”.

Robert Connell, St Kilda and the St Kildans, Thomas D Morison, 1887.

Returning now to our main theme, it may be helpful if I list some of the special skills needed by the inhabitants of St Kilda to maintain their way of life in the particular environment in which they found themselves. I will apologise in advance for concentrating on skills needed more by men than women. They included:

- The ability to come ashore from a boat. Even disembarking at Village Bay was tricky as no jetty was constructed until 1902. You had to clamber out onto a large slab of sloping rock and then make your way to the top of the rock without losing your footing. Getting onto the island of Boreray was far more challenging. A full description of this operation was provided by George Atkinson in 1831, but essentially one man at a time would leap onto a suitable section of a fifteen foot cliff. By the time Atkinson himself came to disembark a sloping “gangplank” of ropes had been put together for his benefit.

George Atkinson, A Few Weeks Ramble among the Hebrides in the Summer of 1831.

- The ability to climb up and down steep or sheer cliffs, and to jump across gaps between two cliffs, making use of ropes for the longer climbs. Male children were introduced to climbing skills at an early age, but were expected to take several years to perfect them.

- The ability to test the strength of ropes prior to use. Ropes were made from various raw materials. Cow hide tended to be favoured most of all, but even cow hide deteriorated over time. The standard testing procedure was to attach the rope to a large boulder and see whether it would break under the strain of four men pulling on it. The testing procedure was normally watched by other members of the community to ensure it was conducted properly.

- Catching and killing sea birds. Enough documentary evidence is available on this intriguing topic to provide material for an entire chapter. To whet your appetite I will simply mention that when catching gannets at night it is important to catch the “sentinel” bird first, the task of surprising the less alert gannets being then much easier, when catching fulmars it is wise to avoid being spat upon by them, and when you get close to a fulmar there is a technique for twisting its neck that will retain the oil in its stomach.

- Carrying eggs. The summit of Stac Lee was a place favoured by gannets for their nests. It was therefore a place favoured by the men of St Kilda for taking eggs. The eggs were carried in boxes on their backs as they made their descent to the sea.

- Blowing eggs. This was one of the skills developed by the islanders after tourists began to visit them in significant numbers. The eggs of many species of birds were blown for collectors, one of the most prized being eggs of the St Kilda wren, a type of wren found nowhere else.

Having said that, I want to share with you two of the legends of St Kilda, the first because it illustrates the tendency for an almost identical legend to become associated with several geographically separate communities, the second because I like it.

The first legend deals with the way in which St Kilda came into the ownership of the MacLeod family. As the MacDonalds also laid claim to the islands it was agreed that a boat race would take place and the islands would be awarded to the crew that first laid a hand on St Kilda. As both boats approached the shore the MacLeod boat was a little way behind, but a member of their crew cut off one of his hands and with his other hand threw it onto the land. The trouble with this tale is that, as shown by Mary Harman, a similar story has been told of two other places in Scotland and also two places in Ireland.

Mary Harman, op. cit. p230.

The other story relates to a place known as the Lover’s Stone or the Mistress Stone, a rocky ledge on a hill on the south side of Hirte from which there is a sheer drop of 135 metres into the sea. A ritual said to have taken place there at some time in the past was described by Robert Connell in 1887 as follows: “In those days a young St. Kildan who wished to make one of the fair maids of the island his own was required to accomplish a most dangerous feat in order to prove possibly the sincerity of his love, but, more probably, his ability to support a wife. The aspirant to the hand of a fair St. Kildan had to climb this giddy, dangerous height, and, planting his left heel on the outer edge, with the sole of his foot entirely unsupported, he extended his right leg forward beyond the other and grasped the foot with both hands, holding it long enough to satisfy the lady and her friends gathered below”.

Robert Connell, St Kilda and the St Kildans, Thomas D Morison, 1887.

Returning now to our main theme, it may be helpful if I list some of the special skills needed by the inhabitants of St Kilda to maintain their way of life in the particular environment in which they found themselves. I will apologise in advance for concentrating on skills needed more by men than women. They included:

-

-

-

-

-

-

Three

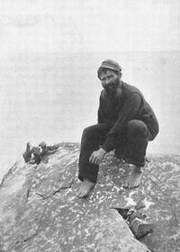

These pictures come from “With Nature and a Camera”, by Richard Kearton, published in 1898.

The whole book is reproduced at this address

The Lover’s Stone