Abandoned Communities ..... Dylife

Many towns and villages in Britain have developed in association with mining activities. When the mines closed such communities suffered economic hardship and some loss of population, especially as people moved away to seek work elsewhere. However, only a few have been abandoned. In most cases those people who stayed have endeavoured to maintain their community, albeit in changed form. The mines have sometimes been replaced by other industrial enterprises, or new services or facilities for tourists have provided opportunities for employment. Alternatively, local people have commuted to jobs in neighbouring towns and cities.

For a good summary of the various outcomes suffered by mining communities read Richard Muir, The Lost Villages of Britain, Book Club Associates, 1985, pp 235-237.

Dylife occupied a remote location in mid Wales, at OS SN862941. When the mines closed near the end of the nineteenth century very little alternative employment was available in the area, and the remaining inhabitants took the decision to move away.

Pronounce it somewhat like "deliver", but with the second syllable sounding “ee”.

The history of mining at Dylife has been outlined by Michael Brown. Additional information about the ownership and management of the mines can be found in an article by CJ Williams.

Michael Brown, Dylife, Y Lolfa, 2005, and CJ Williams, Cobden and Bright, and the Dylife Lead Mines, Welsh History Review, 2002, 21, 75-117. This article can be downloaded free of charge from the IngentaConnect website.

At Dylife there is evidence of lead mining during the Roman occupation. Mining seems to have been resumed during the seventeenth century. It continued in a relatively informal manner and with limited production until the beginning of the nineteenth century. The only episode of interest from this period was a series of events that involved three murders and a hanging. The episode illustrates in extreme form how things may go badly wrong when a breadwinner has to work some distance away from his or her family. A blacksmith by the name of Siôn Jones came to work at Dylife in 1725, leaving his wife and two children at home at Ystumtuen in Cardiganshire. Soon after his arrival in Dylife Siôn Jones began an affair with a farm maid. Several weeks later his wife brought the two children on foot to spend a few days with him. On the surface all went well during their stay, but when his wife and children began the journey home Siôn Jones murdered them and threw their bodies down a disused mine shaft.

Eleven weeks later a group of men were instructed to retrieve some old timbers from the mine shaft, and discovered the bodies. Siôn Jones was put on trial and found guilty of the murder of his wife and children. As his final task as a blacksmith he was ordered to make a hanging frame. With the frame suspended from a gallows Siôn Jones was obliged to sit on a horse's back until the horse was made to move on.

Part of the iron frame and a skull were discovered in 1938. They are kept at the National History Museum, St Fagans, near Cardiff, but may not be on display.

By 1809 the mines at Dylife were managed by two men from Machynlleth, Hugh Williams and John Pughe. In that year 22 tons of lead ore were produced. Williams and Pughe then spent five years obtaining a lease from the landowner, Sir William Watkins-Wynne. The signing of the lease was delayed because they failed to produce satisfactory financial accounts and articles of partnership that would govern their working relationship. They obtained the lease in 1814, and they and their successors continued to operate the mines until the 1850s. But throughout this period financial management continued to be unsatisfactory, and there were repeated difficulties in relations between the two lease holders. When there was a need to purchase new equipment, for example, both men would pay half the cost. Employees were paid twice a week, on separate days, receiving half their wages from Williams and half from Pughe. There was resentment between the two men, with Williams taking the view that Pughe was devoting much less time and energy to the management of the mines than he was.

For a good summary of the various outcomes suffered by mining communities read Richard Muir, The Lost Villages of Britain, Book Club Associates, 1985, pp 235-

Dylife occupied a remote location in mid Wales, at OS SN862941. When the mines closed near the end of the nineteenth century very little alternative employment was available in the area, and the remaining inhabitants took the decision to move away.

Pronounce it somewhat like "deliver", but with the second syllable sounding “ee”.

The history of mining at Dylife has been outlined by Michael Brown. Additional information about the ownership and management of the mines can be found in an article by CJ Williams.

Michael Brown, Dylife, Y Lolfa, 2005, and CJ Williams, Cobden and Bright, and the Dylife Lead Mines, Welsh History Review, 2002, 21, 75-

At Dylife there is evidence of lead mining during the Roman occupation. Mining seems to have been resumed during the seventeenth century. It continued in a relatively informal manner and with limited production until the beginning of the nineteenth century. The only episode of interest from this period was a series of events that involved three murders and a hanging. The episode illustrates in extreme form how things may go badly wrong when a breadwinner has to work some distance away from his or her family. A blacksmith by the name of Siôn Jones came to work at Dylife in 1725, leaving his wife and two children at home at Ystumtuen in Cardiganshire. Soon after his arrival in Dylife Siôn Jones began an affair with a farm maid. Several weeks later his wife brought the two children on foot to spend a few days with him. On the surface all went well during their stay, but when his wife and children began the journey home Siôn Jones murdered them and threw their bodies down a disused mine shaft.

Eleven weeks later a group of men were instructed to retrieve some old timbers from the mine shaft, and discovered the bodies. Siôn Jones was put on trial and found guilty of the murder of his wife and children. As his final task as a blacksmith he was ordered to make a hanging frame. With the frame suspended from a gallows Siôn Jones was obliged to sit on a horse's back until the horse was made to move on.

Part of the iron frame and a skull were discovered in 1938. They are kept at the National History Museum, St Fagans, near Cardiff, but may not be on display.

By 1809 the mines at Dylife were managed by two men from Machynlleth, Hugh Williams and John Pughe. In that year 22 tons of lead ore were produced. Williams and Pughe then spent five years obtaining a lease from the landowner, Sir William Watkins-

One

The remains of Siôn Jones

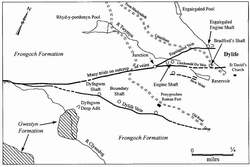

A map of the mines at Dylife

(with thanks to Christopher Williams)

(with thanks to Christopher Williams)