Abandoned Communities ..... Dunwich

Before we move back inland I want to talk about Dunwich. Like Kenfig Dunwich was a prosperous coastal town during the early Medieval period. Indeed it had had an illustrious history during Saxon times. Bishops had been based there, beginning with Felix between 636 and 647, and ending with Aethilwald in the mid ninth century. It was located on the southern shore of what was at that time a splendid natural harbour on the coast of Suffolk.

In common with much of the east coast of England Dunwich suffered at the hands of Scandinavian raiders during the ninth and tenth centuries. However, it recovered well after the Norman Conquest. It is mentioned in the Domesday Book (1086), where it is recorded that three churches existed in the town. From the information provided in the Domesday Book it has been estimated that the population at that time was about 3,000. It included 24 "Franci", thought to be people of French origin who had migrated since the Conquest.

In common with much of the east coast of England Dunwich suffered at the hands of Scandinavian raiders during the ninth and tenth centuries. However, it recovered well after the Norman Conquest. It is mentioned in the Domesday Book (1086), where it is recorded that three churches existed in the town. From the information provided in the Domesday Book it has been estimated that the population at that time was about 3,000. It included 24 "Franci", thought to be people of French origin who had migrated since the Conquest.

The Domesday entry about Dunwich can be seen on the National Archives website. Click on the sample to view the whole entry.

During the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries Dunwich continued to thrive. Three more parish churches were built, and religious houses were established for groups of Grey Friars and Black Friars. A hospital for people with leprosy was built. Everyday life included the rearing of sheep and pigs, and the farming of rabbits, but above all it concentrated on maritime activities. There was a busy shipbuilding industry, and ships from Dunwich were engaged in trading both around the British coast and to many of the countries of continental Europe. Fishing boats brought back catches of herring and sprat from local fishing grounds, but travelled as far afield as Iceland for cod and ling. Many of the ships of Dunwich could be used during warfare. In 1229, for example, King Henry III requested 40 ships from Dunwich "well equipped with all kinds of armament, good steersmen and mariners". After some negotiation it was agreed that Dunwich would in fact supply 30 ships, a contingent that made up about one eighth of the fleet that sailed from Portsmouth in May 1230 to carry on the wars in France.

In military terms Dunwich's finest hour came in 1173. In September that year the Earl of Leicester landed with an army on the Suffolk coast intent on mounting a rebellion against King Henry II. An account of what happened when the Earl of Leicester reached the outskirts of Dunwich is given in the Chronicle of Jordan Fantosme.

See Jordan Fantosme’s Chronicle, ed., trans., and notes by R.C. Johnston. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981.

The Earl announced that he intended to be the friend of Dunwich, but if the people of the town refused to join him "those now living will lose their heads". To back up his threats he ordered gallows to be erected to frighten the inhabitants. The men of Dunwich prepared to defend themselves and even the women were called upon to carry stones to the palisade to be hurled at the enemy. Seeing that there was going to be stiff resistance the Earl of Leicester changed his mind and withdrew his troops early the following morning.

Kenfig was destroyed when the sea dumped very large quantities of sand on it. Dunwich was demolished by the sea in three other ways. The main process was coastal erosion. Erosion of the coast line had been going on ever since Suffolk became separated from the Netherlands. For the last two thousand years the coast line at Dunwich has receded on average one metre a year. In other words the sea shore is now two kilometres west of its position in Roman times. For a decade or two you may not notice much change, though it is likely that higher tides will tend to weaken the lower section of the cliff face. Then a major storm will take away several metres of cliff at once. Two or three major storms will remove a couple of streets, associated housing, and perhaps a church.

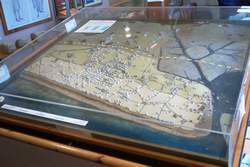

In the museum in today's Dunwich there is a magnificent model of the medieval town, as it might have appeared from the air in the twelfth century. Many houses are teetering on the edge of the cliff. With the benefit of hindsight we know they will not be there much longer. Much of the town is contained between the twelfth century shoreline and a line on the model representing where the cliffs were in the sixteenth century. The rest of the town would fall into the sea over the next couple of centuries. The position of the current shoreline is marked by yellow sticky tape, presumably chosen because it is easily removable.

The sea would also cause havoc by flooding much of the lower part of the town, the area closest to the harbour. Whenever this happened great damage would be done to ships, quays, and the pier, and nearby buildings would be devastated.

In military terms Dunwich's finest hour came in 1173. In September that year the Earl of Leicester landed with an army on the Suffolk coast intent on mounting a rebellion against King Henry II. An account of what happened when the Earl of Leicester reached the outskirts of Dunwich is given in the Chronicle of Jordan Fantosme.

See Jordan Fantosme’s Chronicle, ed., trans., and notes by R.C. Johnston. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981.

The Earl announced that he intended to be the friend of Dunwich, but if the people of the town refused to join him "those now living will lose their heads". To back up his threats he ordered gallows to be erected to frighten the inhabitants. The men of Dunwich prepared to defend themselves and even the women were called upon to carry stones to the palisade to be hurled at the enemy. Seeing that there was going to be stiff resistance the Earl of Leicester changed his mind and withdrew his troops early the following morning.

Kenfig was destroyed when the sea dumped very large quantities of sand on it. Dunwich was demolished by the sea in three other ways. The main process was coastal erosion. Erosion of the coast line had been going on ever since Suffolk became separated from the Netherlands. For the last two thousand years the coast line at Dunwich has receded on average one metre a year. In other words the sea shore is now two kilometres west of its position in Roman times. For a decade or two you may not notice much change, though it is likely that higher tides will tend to weaken the lower section of the cliff face. Then a major storm will take away several metres of cliff at once. Two or three major storms will remove a couple of streets, associated housing, and perhaps a church.

In the museum in today's Dunwich there is a magnificent model of the medieval town, as it might have appeared from the air in the twelfth century. Many houses are teetering on the edge of the cliff. With the benefit of hindsight we know they will not be there much longer. Much of the town is contained between the twelfth century shoreline and a line on the model representing where the cliffs were in the sixteenth century. The rest of the town would fall into the sea over the next couple of centuries. The position of the current shoreline is marked by yellow sticky tape, presumably chosen because it is easily removable.

The sea would also cause havoc by flooding much of the lower part of the town, the area closest to the harbour. Whenever this happened great damage would be done to ships, quays, and the pier, and nearby buildings would be devastated.

One

The chapel of the hospital for people with leprosy

A twelfth century seal from Dunwich. It depicts a ship of that time, with castles at the fore and aft of the vessel.

Another version of the twelfth century ship

Dunwich as it may have been around 1200