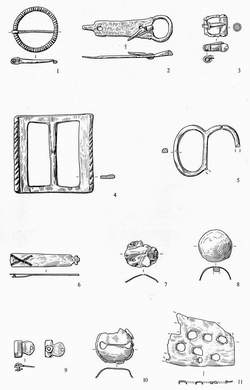

Copper alloy objects, including a brooch, several buckles, and a rumbler bell

Pottery from the rubbish pit in toft 10, including pieces of cooking pots, a bowl, a storage jar, and jugs

The site of Grenstein, looking towards the north

Looking south. Tom Butler-

A relatively limited range of building materials were available in medieval East Anglia. The main materials found during the excavation of Grenstein were unbaked clay, timber, and flint. In addition a few pieces of brick turned up. The remains of clay walls were found in all the excavated buildings. The clay would have been dug from local clay pits and then formed into blocks. Clay walls can be strong and durable provided they are kept dry. Deeply overhanging eaves are needed to prevent the splash of rain water damaging the lower part of the walls.

Flints were rarely used in buildings at Grenstein except as the foundation courses for walls. They were used in the paving of the farmyards at toft 10 as well as forming the surface of the main street.

Objects found during the excavations included:

· An Edward I penny, almost mint and thought to date from 1279-

· Various copper artefacts.

· Iron objects including knives, tools, locks and keys, household items such as candle holders, buckles, and horseshoes.

· Stone objects, including hones for sharpening knives, and querns.for grinding grain.

· Sherds of pottery, most manufactured in north east Norfolk, probably at Grimston, but also some imported from other parts of England or the continent of Europe. Some of the pottery may date from the twelfth century, but most of it would have been made in the thirteenth and fourteenth century. Some pieces, such as fragments of bowls and cooking pots, made probably in the fourteenth century, were discovered under the paving of the farmyards. The paving must therefore have been laid down in the later fourteenth century or perhaps in the fifteenth century.

Pieces of bone were also found. These give indications of some aspects of the diet of people at Grenstein as well as revealing what animals and birds lived in their environment. Most of the animal bones were horse, ox, sheep, goat, or pig, but there were a few bones from dogs, domestic cats, and hares. The interpretation of the bird bones is less certain, but most of them probably came from domestic fowl and domestic geese, with a few from raven, rook, and mallard.

As we have seen there is evidence that toft 10 survived longer than neighbouring

tofts. The decline of Grenstein is likely to have been gradual. The Black Death in

1348-

My visit to Grenstein took place on the first day of haymaking. The farmer, Tom Butler-