Abandoned Communities ..... Binnend

The population of Binnend had started to decline by 1892, when the mines closed and most work ceased. Between the census of 1891 and that of 1901 the male population of the “landward” part of Burntisland parish fell from 616 to 353 and the female population from 565 to 400. Presumably single men would have been most likely to move away in search of alternative work, and in some cases married men would have moved too, leaving their families at Binnend or arranging for their families to join them at a later date. Some of them found jobs in the coal mining industry. In particular a group of men from Binnend were taken on at the Raith Parrot mine where an industrial dispute had resulted in the departure of the existing mining staff.

In 1893 a visit by a recruiting sergeant to Binnend resulted in several men joining the army.

Before long a significant number of dwellings at Binnend became unoccupied, yet the village, at least the part at High Binn, continued to survive for several decades. During World War One some of the houses were taken over by the Admiralty for staff working at Rosyth, and troops were given accommodation in the school building.

After that war the village enjoyed something of a revival. Some of the houses were offered to women whose husbands had been killed in the war. There were new opportunities for employment in the shipyard and aluminium works at Burntisland. In addition, the village became popular as a place where people would come to stay for their summer holidays. The school building, said to have a good quality wooden floor, continued in use as a venue for dances and concerts.

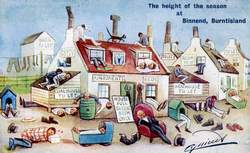

The postcard reproduced on the left suggests that overcrowding often became a problem during the holiday season.

Reminiscences of people who lived as children in Binnend in the 1920s, or took their holiday there, can be read at this address, and also in Iain Sommerville (Ed.), Burntisland Voices, Burntisland Heritage Trust, 2005, chapter 4. Topics often mentioned in these reminiscences include the toilet facilities, the entertainment and gossip available at the school building, opportunities for intimate contact with members of the opposite sex, deliveries of bread, groceries, ice cream, and coal, and serving as caddies on the golf course on the other side of the road to Kinghorn.

By 1931 it was clear to the owners of the village, the Whinnyhall Estate, that it would not be possible to upgrade the houses to a satisfactory modern standard. The houses lacked an individual water supply or sanitation, and there was no gas or electricity. The decision was taken to close the village, in the sense that regular maintenance no longer took place. In due course the roofs of unoccupied dwellings were removed so that the estate would not be liable to rates on those houses. Nevertheless some people stayed on, and in 1950 there were still about 16 residents.

By 1952 there were just two couples in Binnend, living in adjacent houses. Mr and Mrs MacLaren had originally come to Binnend to run the shop. They had put their name down for a council house in Burntisland after the shop had closed early in World War II. They moved away in that year, presumably to a council house.

The last survivors were Mr and Mrs Hood. Mrs Hood died in 1954, and Mr Hood, then aged 74, moved to Newcastle to live with his son.

In 1893 a visit by a recruiting sergeant to Binnend resulted in several men joining the army.

Before long a significant number of dwellings at Binnend became unoccupied, yet the village, at least the part at High Binn, continued to survive for several decades. During World War One some of the houses were taken over by the Admiralty for staff working at Rosyth, and troops were given accommodation in the school building.

After that war the village enjoyed something of a revival. Some of the houses were offered to women whose husbands had been killed in the war. There were new opportunities for employment in the shipyard and aluminium works at Burntisland. In addition, the village became popular as a place where people would come to stay for their summer holidays. The school building, said to have a good quality wooden floor, continued in use as a venue for dances and concerts.

The postcard reproduced on the left suggests that overcrowding often became a problem during the holiday season.

Reminiscences of people who lived as children in Binnend in the 1920s, or took their holiday there, can be read at this address, and also in Iain Sommerville (Ed.), Burntisland Voices, Burntisland Heritage Trust, 2005, chapter 4. Topics often mentioned in these reminiscences include the toilet facilities, the entertainment and gossip available at the school building, opportunities for intimate contact with members of the opposite sex, deliveries of bread, groceries, ice cream, and coal, and serving as caddies on the golf course on the other side of the road to Kinghorn.

By 1931 it was clear to the owners of the village, the Whinnyhall Estate, that it would not be possible to upgrade the houses to a satisfactory modern standard. The houses lacked an individual water supply or sanitation, and there was no gas or electricity. The decision was taken to close the village, in the sense that regular maintenance no longer took place. In due course the roofs of unoccupied dwellings were removed so that the estate would not be liable to rates on those houses. Nevertheless some people stayed on, and in 1950 there were still about 16 residents.

By 1952 there were just two couples in Binnend, living in adjacent houses. Mr and Mrs MacLaren had originally come to Binnend to run the shop. They had put their name down for a council house in Burntisland after the shop had closed early in World War II. They moved away in that year, presumably to a council house.

The last survivors were Mr and Mrs Hood. Mrs Hood died in 1954, and Mr Hood, then aged 74, moved to Newcastle to live with his son.

Four

The Square, at the western end of the High Binn

Part of The Square in April, 2008

Overcrowding during the holiday season